Exploring diversity in the Venture Capital (VC) industry with an LGBTQ+ lens

Author: Ioto Iotov

That there is generally a lack of diversity in VC is a badly kept secret. Report after report talks about the fact that the industry, particularly at the decision-making level (which for a VC firm is a Partner), is not representative of the broader population.

Homophily-driven biases are the tendency to associate with people who are like you. These biases are inherent and strong. Having diversity at the GP level is therefore important to overcome this phenomenon. GPs act as gatekeepers of capital, ultimately deciding who gets funded. Because of the power of homophily, having a non-representative GP decision-making level could lead to excluding business founders who are unlike the GPs.

Diversity VC states in its “The Equity Record UK” that “when investors predominantly come from similar homogenous groups, their investments reflect and reinforce their own experiences and biases, inadvertently sidelining a vast pool of untapped entrepreneurial potential.”

Getting the answer to this more nuanced question was challenging: what percentage of Limited Partner (LP) money is directed towards LGBTQ+ led GPs? Much of the research to date has focused on diversity as measured along gender and race, excluding that of diversity based on sexuality. Therefore, for the purposes of this piece, I drew on the major body of research on diversity along the lines of gender and race and made inferences from this. If we don’t measure something, we can’t gather the data - data that is needed to make properly informed decisions.

Before delving into the findings, it is worth explaining the players in the VC landscape. The venture landscape is made up of several participants, but at its heart are three parties:

- The bank: Limited Partners or LPs are the ultimate allocators of capital. They are generally family offices, UHNWI, and institutions (insurance, pensions, and endowments).

- The distributor: Venture Capitalists or VCs are the recipients of LP capital and the ones who decide which companies to invest in or not.

- The recipient: Venture-backed companies. These are companies which receive venture funding from the VC.

Money flows down the trinity, like a melting snow cap, from largely concentrated sources (LPs) to rivers (VCs) and ultimately into trickles (the VC-backed companies).

Setting the scene

VCs remain strongly non-representative of the wider population: they are predominantly male (~91%) and white (~86%). In Elizabeth Edwards’ piece for Forbes (Check Your Stats: The Lack Of Diversity In Venture Capital Is Worse Than It Looks), she found that, when considering the true decision makers in Venture, (defined as those at partner level) 93% were white males.

On sexuality, Mountside Ventures and i3 found in the report “The Definitive Guide to Venture Capital Fund-of-Funds 2023” that only 2% of the LPs surveyed (>100 global FoF) identified as LGBTQ+. This contrasts starkly with the wider population, with the Stonewall report (“Rainbow Britain”) showing that ~30% of Gen Z Britons identify as non-straight. This percentage increased to ~ 50% when this was defined more loosely. The 2% from the Mountside report also under-represented older population groups, with LGBTQ+ identification across generation groups, per the Stonewall report, at 18% for Millennials, 13% for Gen X and 9% for Baby Boomers. At best, the 2% indicates an underrepresentation of 4.5x and 15x at worst.

In Paul Gompers and Sophie Wang’s working paper for Harvard Business School (“Diversity in Innovation”), they state:

“The demographic patterns and trends surveyed in this paper have highlighted the overall lack of gender and ethnic diversity in both entrepreneurship and venture capital. Women have entered into entrepreneurship and venture capital at rates much lower than their entry rates into other highly compensated professional fields such as medicine or law. The representation of women in science and technology advanced degrees (as a precursor to entrepreneurship) and MBAs (as a precursor to entry into venture capital) 36 are again much higher than the representation of women in the innovation sector. Also, the relative percentage of both sectors who are female has not increased measurably over the past twenty-five years. Similarly, the fractions of Hispanics and African Americans are also much lower than their general population compositions, despite the improvements in their educational attainments in advanced science and engineering degrees or MBA programs. While the experience of Hispanic entrepreneurs and venture capitalists has improved some, there has been no increase in the representation of African Americans in either.”

Why is the status quo a problem?

Without all companies having a fair go at receiving venture funding, given the networked nature of venture investing, we continue to perpetuate ingrained advantage, privilege and prejudice. Two major sources of venture capital are pension and insurance companies. These institutions are custodians and recipients of the wider (duly diverse) population’s retirements and premiums. So, we have diverse sources of capital being amalgamated and handed out to a non-diverse set of managers. Thirdly, the business case; diverse teams outperform non-diverse ones. This is true too for venture firms.

VCs decide not just what ideas get funded but who gets funded. Warm introductions to VCs are the most likely route to getting VC funded. Some VCs specifically state they only take meetings and, by extension, invest in companies that come through warm introductions. In the British Business Bank “UK VC & Female Founders Report” it was found that warm introductions were 13 times more likely to reach the investment recommendation stage, often the last stop in the journey to get venture funding. Warm introductions were defined as the company being recommended to the VC by someone in the VCs network.

Following this approach means they only invest in companies within their network. This results in funding business with founding teams that most likely look like the VC.

Intuitively, it is understood that diversity of thought and experience leads to fewer stones unturned and greater robustness of conversation during decision-making, which would suggest improved outcomes. Studies are increasingly showing that increased diversity in teams leads to better outcomes. The business case for inclusion remains strong and is empirically supported.

In a follow-up to their 2017 research, Wang and Gompers asked the question as to whether increased diversity leads to better outcomes. Better outcomes in the world of VC are measured as better returns. Their diversity findings were focused on gender; sexuality was not considered.

They show that firms with partners with a higher proportion of daughters hired more females into the GP. They state:

“The relative effect of having on average a daughter rather than a son by existing partners increases the female hired ratio by 1.93%, compared with a base rate of 8.03%. It lifts deal success by about 2.88%, given the overall success 24 rate at 28.7%. It also translates to an increase of 3.20% in net IRR compared to average fund returns of 14.1%.”

Wang and Gompers point out that the most likely explanation for the persistent representation of women in VCs is homophily. Therefore, given this innate bias, unless we change the composition of the decision-makers in VCs or collectively enact policies to overcome this bias, we are unlikely to see significant change. The data supports this; looking at female involvement in the VC industry, Wang and Gompers found that the percentage of female venture capitalists had not increased measurably over the last 25 years.

I made an attempt to find the data and answers to the question about LGBTQ+ representation at VCs, including scouring the internet for any specific research (little to none). I reached out to the Chief Investment Officers and PR representatives of some of the world's largest allocators to venture and private equity, but with no luck in soliciting responses. Is no one asking the question?

Including only some means excluding the rest

We know that the lack of diversity of VCs is mirrored by the founders and entrepreneurs in the companies being backed by VCs. This article does not delve into causation and correlation but highlights this fact.

It is those VC-backed companies that touch millions of stakeholders. Be it employees, service providers, and members of the communities, states, and countries in which they operate. A healthy early-stage ecosystem is essential for any population to not just thrive but to continue to exist.

Companies are the economic backbone of our commercial systems. And, for most of the world’s working population, they are the source of their income. Issues at the company level reverberate through the rest of society. It is, therefore, imperative that we ensure the health of the system.

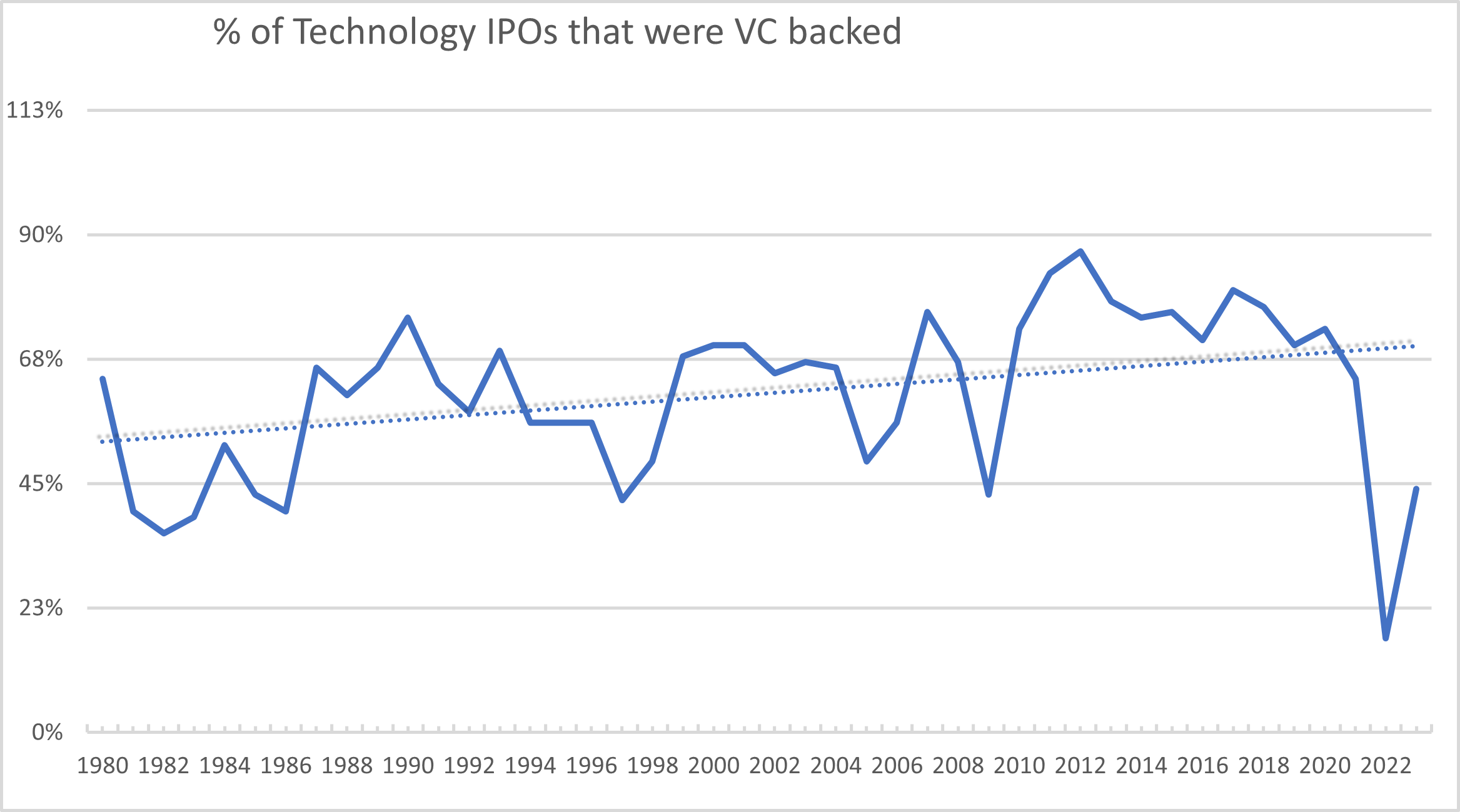

Venture-backed businesses represent a very small fraction of all start-up businesses, with an HBR measure putting it at <1% for US startups. These few, however, result in significantly outsized end results. Companies like Google, Intel, Facebook, Amazon and Apple were all recipients of venture funding before going public. The average percentage of technology companies that had an IPO between 1980 and 2023 and were VC backed was 60%. Of the 3,320 technology companies that had an IPO, close to 2,000 received venture funding. Therefore, venture capitalists play an outsized role in shaping the business world, funding only 1% of startups, but having financed 60% of technology companies that had IPO’s. Listed businesses are generally larger than their non-listed counterparts. An inference can, therefore, be made that VC-backed companies generally grow into larger businesses than non-VC-backed companies and, by extension, have a greater impact on society.

The trendline (dotted blue line) graphed above shows that Tech businesses that IPOs are increasingly backed by VCs. That means tech companies that IPO are ever more likely to have had VC backing.

It is essential that VCs, as custodians of capital, ensure that the best businesses are being funded. Not just those that look like them or are within their own circles, which, as we know, tend to be relatively homogenous.

Are there positive signs? Yes, intention is there. In Mountsides Report it was found that 1 in 4 FoF (funds that invest into multiple VCs in a single fund) have a requirement towards diversity investing. The areas of diversity most in focus were women and ethnic minorities. However, the data is not there to make meaningful inferences about the funding of LGBTQ+ led VCs.

What can be done? LPs are the ultimate capital allocators. They direct where the billions of dollars earmarked for venture go. It is, therefore, essential that the LPs first identify that they have a responsibility to direct capital in a way that stops the preference of one group over another. Capital must find its way to the best and brightest, not the connected and fortunate.

Bodies working within the space, such as the British Venture Capital and Private Equity Association and the CFA UK, should be championing this issue. They are uniquely placed to start asking the questions and collating the answers.

To address the issue, we need to quantify the problem. I call on LPs to start measuring and reporting on whom they allocate their capital to. These dimensions need to be broad and include diversity across its multiple dimensions. Once we have the data, we can assess and respond adequately, being fully informed.

VCs have an outsized impact on the overall business landscape through the businesses we invest in. We indirectly touch many lives through the companies in our portfolios. Be it through employment, product usage or the indirect benefit of the taxation paid to governments, our decisions echo throughout society. We have a responsibility to be judicious custodians of capital. We are responsible for acting in the interest of a wide and varied stakeholder base. We, too, need to ensure that we are investing in the best possible ideas, people and businesses. That is why we should look to lower the barriers to those historically left out of the system.