Author: John Citron, CFA

How would the similarities and differences between Ben Graham's time and today's investment environment affect his writings? And, what do you think Graham would change in a ‘Security Analysis' 2017 edition?

“Behind it all is surely an idea so simple, so beautiful, that when we grasp it – in a decade, a century, or a millennium – we will all say to each other, how could it have been otherwise?” – John Archibald Wheeler, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (1986)

The totemic achievement of Security Analysis was to identify the set of fundamental principles which had always governed investing and to explain them to investors who had previously depended on other explanations to guide their efforts. It is easy to forget but in the 1920s the most famous stock picker in America may well have been the astrologer Evangeline Adams who claimed over a million followers1.

Graham’s most famous conclusions were articulations of immutable truths. The notion that successful investing requires a margin of safety whereby an investor ensures “a stock is worth more than he pays for it”2 is logic that must necessarily flow from foundational concepts like price and value. Similarly, the metaphor of Mr. Market takes a timeless truth about human psychology and simply applies it to the specific context of the stock market.

In this sense little about today’s investment environment could change Graham’s conclusions since most were not dependant on parochial circumstance. Nonetheless there are two approaches that allow us to identify differences between today’s investment environment and that of Ben Graham’s time which might have provoked new writing.

The first is to consider an instance where his conclusions were not explanations of universal principles but instead were reliant on the available evidence. Specifically we look at his outright rejection of growth investing and consider whether changes in the available data and investable universe might have nuanced his views.

Secondly we consider new areas into which his ideas with universal reach might be extended. While there are many candidates, we focus on imagining the advice he might give to an investment industry that has evolved to a size and scale beyond what would have been imaginable at the original time of writing.

Corporate Maturity & The Passage of Time

“[W]e must start with the emphatic but rather obvious assertion that the investor who can successfully identify such “growth companies” when their shares are available at reasonable prices is certain to do superlatively well with his capital…But the real question is whether or not all careful and intelligent investors can follow this policy with fair success.”

– Ben Graham, Security Analysis (Sixth Edition), P. 368

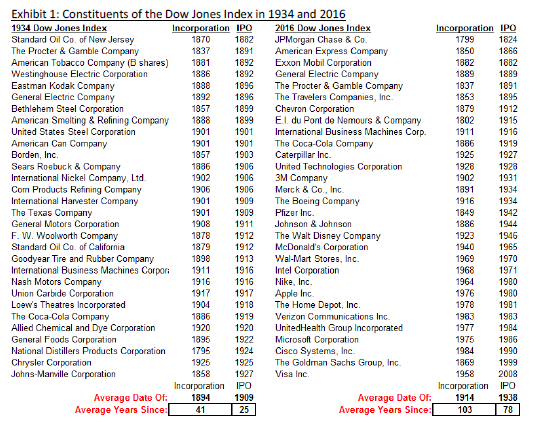

Although the New York Stock Exchange was a century old by the time Graham was writing, the average company within his investable universe lacked maturity both as a corporation and as a listed entity. The table below attempts to quantify this difference by comparing the constituents of the Dow Jones Index in 1934, the year Security Analysis was published, and 20163. The average company in the 1934 Dow was 41 years old and had been listed 25 years. By contrast the average company in 2016 was more than twice as old and had been listed half a century longer. This constitutes a clear difference between Graham’s time and today and we can consider how it might have influenced one of his more famous conclusions.

Chapter 28 of Security Analysis draws the distinction between growth and value as investment styles and argues that only the latter, value, is likely to be practiced by the ordinary investor with any degree of success. While it is unlikely that Graham would have reversed this conclusion, the longer histories of today’s corporations might have led him to a more nuanced distinction. In particular while he would remain sceptical of businesses with no history of profitability but forecast to achieve rapid future earnings expansion, it is possible that his stance on higher quality compound growth businesses might become more accommodating.

Graham has two main arguments against growth as an investment style:

i) There are almost no genuine ‘growth’ businesses, properly defined.

ii) Even if growth companies could be identified, they are impossible to value.

Graham accepts a definition of ‘growth companies’ as those “whose earnings move forward from cycle to cycle”4. However, in the context of the 1930s stock market, he argued that most companies given the growth title by his peers had not in fact been around long enough to deserve the accolade: “this distinction is in reality based on performance during a single cycle, [so] how sure can the investor be that it will be maintained over the longer future?”5. Here Graham explicitly uses the short operational history of the typical listed corporate in his investable universe as a reason for believing that growth investing lacks reliable foundations. Given the average listed corporate today now has a much longer operational history than a single cycle, we can consider whether the additional evidence might have changed Graham’s mind on his first objection.

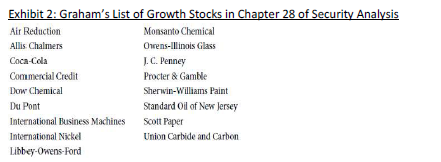

In fact, our longer time horizon almost immediately undermines Graham’s argument since in Security Analysis he gives a list of stocks incorrectly labelled as growth investments and with hindsight we can see that it almost entirely consists of businesses which went on to consistently grow earnings for the next seventy years. His list is shown below and all except Allis-Chalmers and Libbey-Owens-Ford live on as blue chip investments either under their own name or within their acquirers (for example Scott Paper/Kimberley Clark). These businesses may have only grown earnings through a ‘single cycle’ but we can now see that the fact that this cycle encompassed the Great Depression of 1929 was in fact a strong indicator of their merit as “growth” names.

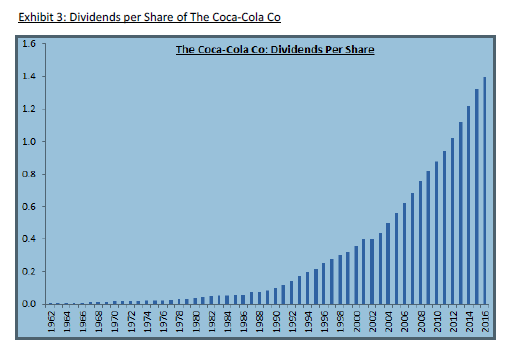

More broadly our ability today to look back over longer corporate histories clearly influences our judgements as to what can be fairly considered a growth stock. Whereas Coca Cola might have seemed mislabelled as a ‘growth’ name in 1934, we can now see a company that has paid a dividend every quarter since 1920 and has grown that dividend for the past fifty-five consecutive years. It is difficult to believe this sort of example would not have impressed Graham given he continually emphasises the importance of a long dividend track record as evidence of a business’ earnings power, notably going as far as to suggest that 20 years of continuous dividend distribution should be demanded before a stock is considered for investment 6.

Examples like Coca-Cola run counter to Graham’s general argument that all businesses eventually revert to an unimpressive mean. They are a direct response to the paradox that he thinks curses the growth investor: “if he chooses newer companies with a short record of expansion, he runs the risk of being deceived by a temporary prosperity; and if he chooses enterprises that have advanced through several business cycles, he may find this apparent strength to be the harbinger of coming weakness”7.

Of course we cannot blindly extrapolate prior dividend increases into the future and an investor must undertake fundamental analysis to understand the intrinsic earnings power of the business. In the case of Coca Cola this means understanding whether its brand, recipe and distribution are still relevant in the modern consumer marketplace. However, it does seem plausible that examples on this scale might have persuaded Graham to relax his first objection to growth as an investment style, namely that no companies truly meet the growth definition. And if Coke alone seems like insufficient evidence then we can add businesses such as Johnson & Johnson, 3M, Parker-Hannifin, Procter & Gamble, Genuine Parts, Emerson Electric and Dover, all of whom who have managed continual dividend increases for at least as long, to reinforce the case.

If Graham was willing to accept that it is possible to identify some companies which we can confidently forecast to grow earnings over successive cycles then his second objection, that even if we can identify growth stocks we cannot value them, also becomes less problematic. In Chapter 5 of Security Analysis, entitled Classification of Securities, Graham rejects the traditional categorisation of securities, based on their structure, as either common stocks or bonds. Instead he argues that securities should be classified by their economic substance. The growth stocks we have been discussing have a fairly clear economic substance, namely they represent a growing perpetual income stream. This kind of income stream we are able to value using tools that Graham gives us, particularly those related to fixed income investing and preferred stock. It should also be relatively straightforward to establish a margin of safety for these names by establishing at what valuation the market is, incorrectly, suggesting that they do not offer future growth.

If Security Analysis were rewritten today, it would certainly not have transformed into a treatise advocating growth investing. Indeed, Graham’s scepticism on “newer companies with a short record of expansion”8 would likely be more pronounced than ever at a time when such businesses are in particular vogue. There are 67 companies in the US valued at over $1bn despite having never made profits9 and Graham would advocate avoiding them all. Our argument is instead the weaker one, that his attitude towards one category within the growth umbrella would have softened to the point where an updated edition might accept that it is possible for the ordinary investor to invest in such stocks while retaining a margin of safety.

Professionalism and the Investment Industry

“Although the idea of giving investment advice on a fee basis is not a new one, it has only recently been developed into an important financial activity” – Ben Graham, Security Analysis (Sixth Edition), P.261

The second major change we can identify in the years since Graham wrote Security Analysis is the exponential growth of investment as an industry in its own right.

The quote at the top of this section nicely summarizes how nascent the industry still was at the time of writing and other data points also reinforce its immaturity. America’s first mutual fund, Massachusetts Investors Trust, had only been launched 10 years previously. The Financial Analysts Federation, the predecessor of the CFA institute, was more than a decade away from coming intoexistence. Blackrock would not be founded for another fifty-five years.

This complete lack of a formalized investment industry represents a clear difference between today’s investment environment and that of Ben Graham’s time. While the mere existence of a difference does not guarantee he would have changed his writing, in this case there is evidence to suggest that Graham would have been interested in including new chapters to address the modern profession.

In the opening paragraph of Security Analysis Graham observes that “the prestige of security analysis in Wall Street has experienced …an ignominious fall”10. This is an early hint that he cares about the reputation of the industry and is hoping his work will help prevent a repetition of past disgraces. This theme echoes throughout the book, for example his famous distinction between speculation and investment can be seen as an implicit guide to what someone offering investment services can reasonably promise to their client and what they cannot. Given this evidence it seems easy to imagine he would want to offer advice to today’s industry. Therefore, the difference we have identified would likely have led to updated chapters.

Although we can only speculate what advice Graham would have given, we can look at the example he set in his own life for inspiration. Based on this we can imagine the new chapters would at the very least include an exhortation for those working within the industry to engage in debate with their peers to improve the profession and also to give their time to educate those outside the industry looking to understand the principles of investment.

The defining characteristic of Graham’s professional career was his tendency to articulate his thoughts on investment in public, whether through his teaching, his books or his prolific article and letter writing. This can be seen in a professional life bookended by the 19-year old Graham submitting his first article “Bargains in Bonds” to The Magazine of Wall Street11 and the 80-year old Graham appearing as a keynote speaker at an investment industry conference12. In between his Columbia Business School teaching career was a clear demonstration of his desire to help spread the discipline that he had invented and it was the material from this course, taught alongside David Dodd, that was later synthesized into Security Analysis. If Ben Graham were updating the work today he would directly address the hundreds of thousands of investors working within the industry and his message would be to engage, to educate and to enjoy working within such an interesting profession.

Indeed, such was Graham’s desire to engage as widely as possible that we might go so far as saying that if he was able to update Security Analysis today it would not be a book at all. Instead we can imagine it as an online course with accompanying YouTube tutorials, such is the difficulty in imaging Graham turning down the opportunity that modern technology affords to reach a wider audience. To that extent someone like Aswath Damodaran of NYU, teaching equity valuation to thousands

online, is as real an heir to Graham as those practising value investing day to day.

Posthumous tribute

Posthumous tribute

“Forty years after publication of the book that brought structure and logic to a disorderly and confused activity, it is difficult to think of possible candidates for even the runner up position in the field of security analysis.”

Warren Buffett, Obituary of Ben Graham, Financial Analysts Journal (Vol. 2, Issue 9, 1976)

The thought experiment we have conducted allows for some evolution in both the interpretation and application of Graham’s teachings. However, we must also be clear that the universality of Security Analysis’ most famous insights, few of which we have touched upon, far outweigh any changes that we have been able to imagine. As such Buffett’s posthumous tribute to Graham, quoted above, still seems to hold true even 83 years on. The ideas expressed here are hopefully in the spirit of Graham’s enthusiasm for debate within the profession and so he could have enjoyed them as such and no doubt responded to those he found disagreeable.

Enter the 2019 CFA UK and Brandes essay competition

1 http://hshm.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/2014-levine.pdf P3 and P9.

2 Graham, Benjamin and Dodd, David L. Security Analysis, Sixth Edition. P372.

3 Data from https://www.globalfinancialdata.com/ and http://som.yale.edu/faculty-research/our-centersinitiatives/international-center-finance/data/historical-newyork

4 Graham, Benjamin and Dodd, David L. Security Analysis, Sixth Edition. P369.

5 Graham, Benjamin and Dodd, David L. Security Analysis, Sixth Edition. P369. My emphasis.

6 Graham, Benjamin. The Intelligent Investor, Fourth Edition. P115.

7 Graham, Benjamin and Dodd, David L. Security Analysis, Sixth Edition. P370.

8 Graham, Benjamin and Dodd, David L. Security Analysis, Sixth Edition. P370.

9 Data from Bloomberg

10 Graham, Benjamin and Dodd, David L. Security Analysis, Sixth Edition. P61.

11 https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/files/a-century-of-ideas.pdf P.31

12 http://www.cfapubs.org/doi/abs/10.2469/faj.v32.n5.20?src=recsys